Global Intercultural Pedagogy

Overview

Changes in political and social policy along with advances in communication and technology have accelerated interaction and interrelationship between people from different cultures (Sorrell, 2). In higher education, we have to consider how to foster learning and development with and between students who are culturally different, preparing them to equitably solve global pressing challenges.

Given that the increase in access to higher education institutions for more diverse student populations has not correlated with an increase in success as measured by retention, graduation or engagement data (Lee, 5), we must critically interrogate our intercultural pedagogical practices.

This module offers resources and specific strategies for educators to critically reflect on intercultural communication and classroom practices in order to highlight and value cultural difference as a part of the classroom content. As faculty begin to develop a skill set to teach interculturally, it will provide a role model for students to develop these skills as well. This approach reduces the need for students from different cultural backgrounds to assimilate to the dominant cultural norms in the classroom. With this in mind, we invite you to explore the resources on this page and incorporate many of the suggested approaches into your teaching practices.

This article covers:

- Introduction

- Teaching Tools

- Supportive Resources

Introduction

What is Global Intercultural Pedagogy?

Global Intercultural Pedagogy is a set of teaching approaches that respond to the needs of learners from different cultural backgrounds, such as international students and domestic immigrants (Lee). In this approach, faculty strive to explicitly communicate the classroom agreements, structures and values with an appreciation for cultural pluralism (Leiva-Olivencia). As educators implementing this pedagogy, we consistently engage in critical reflection of our own worldviews and bring empathy for cultural differences.

Definitions

Cultural Identity

Our situated sense of self that is shaped by our cultural experiences and social locations. This identity is constructed through the languages that are spoken, the stories that are told, and engagement with norms, behaviors, rituals and nonverbal communication. This identity can be perceived, imposed or self-defined (Lee, Sorrels).

Ethnocentrism

The idea that one’s own group’s ways of thinking, being and acting in the world is superior to others. One who adopts this idea will use the standards in their own culture to assess other cultural groups. Expressing that beliefs, ideas, values, and practices of cultures other than one’s own are wrong or strange (Sorrels, Guy-Evans)

Ethnorelativism

The ability to navigate cross-cultural experiences without centralizing one’s own culture. Includes the ability to adapt and accommodate to others (Bennett).

Globalization

refers to the increasing connectedness and interdependence of world cultures and economies due to changes in technology and trade. Includes intensification of interaction and exchange among people, cultures and cultural forms, which leads to shared interests and resources as well as greater intercultural tensions and conflicts (Sorrels, National Geographic).

Intercultural communication

the study and practice of communication across cultural contexts, applying equally to domestic cultural differences such as ethnicity and gender and to international differences such as those associated with nationality or world region. Focuses on the recognition and respect of cultural differences and seeks the goal of mutual adaptation leading to biculturalism rather than simple assimilation (Bennett).

Intercultural sensitivity

A term that was created to describe effective communication skills across cultures which involves the ability to make complex perceptual discriminations among cultural patterns. “Emphasizes the ability to adapt to others in cross-cultural situations with empathy” (Bennett). The outcome of these interactions are beneficial for all parties involved.

Hidden curriculum

Informal learning through socialization which is considered part of the informal learning experience. May include unwritten rules, norms and values along with unspoken expectations that lead to success in the dominant culture environment (Elliot, Chatelain, Unesco).

Positionality

A relational concept which describes how differences in social position and power shape identities and access in society. Impacts the experiences, understanding and knowledge of oneself and the world (Misawa, Sorrels).

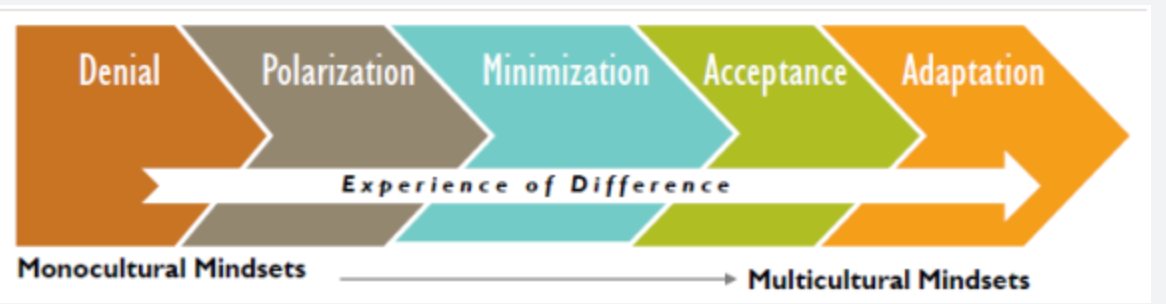

Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity

This model is a grounded theory based on constructivist perception and communication theory, created by Dr. Milton J. Bennett. The continuum illustrated below assumes that boundaries of “self” and “other” are constructed to guide our experiences of intercultural events. The research process gathered observations of students over the course of months and sometimes years in intercultural workshops, classes, exchanges, and graduate programs. Using an elaboration of grounded theory, observations were organized into six stages of increasing sensitivity to cultural difference (Bennett & Bennett).

The stages were created to help guide intercultural training programs and are the basis for the diagnostic tool called “The Intercultural Development Inventory” or IDI. Moving from more enthocentric to more ethnorelative stages or orientations on the continuum hinges on continuing to develop the ability to recognize one’s perception of the world due to one’s own culture and be able to acknowledge different perspectives with appropriate empathic communication.

Denial

The failure to perceive the existence or the relevance of culturally different others. Disinterest or dismissive of intercultural communication. No structural policies or procedures to recognize cultural diversity in a work setting.

Defense

Ability to perceive cultural difference more fully than in Denial, but likely to blame this perceived difference for societal challenges. Critical of norms and behaviors of other cultures, with labeling of “us” and “them”. In this category, one can also exotify other cultures and take on ineffective allyship based on exaggerated stereotypes.

Minimization

Cultural difference is minimized in favor of finding similarities between self and others, often characterized by assumptions that one’s own experiences are shared by others. There is the potential in this stage to exaggerate the benefits of equal opportunity, thus obscuring the operation of dominant cultural privilege.

Acceptance

Consciousness of themselves and others in cultural contexts that are equal in complexity but different in form. Curiosity about cultural difference, with the likely conclusion that the difference is not bad or good. Limited knowledge about other cultures limits the ability to adapt behavior during cross-cultural interactions.

Adaptation

Involves “perspective taking”, allowing one to experience the world as if participating in another culture. Empathy is developed as one can exhibit authentic and appropriate behavior in an alternative culture, but without the flexibility to incorporate one’s own cultural behavior.

Integration

The ability to integrate cultural difference into communication, shifting between in-context and between context states. One’s experience of self allows for movement in and out of different cultural worldviews.

Key Takeaways

The goal of global intercultural pedagogy is for both faculty and students to cultivate and incorporate “multiple readings of reality” leading to authentic interaction, exchange, and dialogue; this practice will set the stage for the educational outcomes of open, flexible, and inquisitive thinking between all members of the classroom community (Trebisacce). With these outcomes, students and faculty can move from communicative competence in one’s own cultural context to communicative competence across cultures (Bennett). This helps increase empathy and understanding as well as avoid asking students to assimilate to the classroom experience. There can be a temptation to focus on “global skill sets” for the workplace (Halualani) which do not interrupt power differentials and dominant culture ideology. There might also be a temptation to tokenize students from certain cultural backgrounds, asking them to educate us about their practices. Instead, intercultural pedagogy centers discourse on identity, experience and alterity across numerous forms of difference from a place of critical reflection and the development of authentic relationships with people from varying cultural backgrounds.

“Intercultural pedagogy is about challenging ourselves and our students to interrogate the way in which we claim or resist authority and to teach one another to examine the unspoken assumptions upon which our sense of identity and interrelation, as well as self and other, is based.” (Lee, 2017)

Teaching Tools

Critical Reflection

Intercultural pedagogy relies on the reflective process, taking time to reflect on interpretations and reactions regarding student behavior inside and outside the classroom. It brings awareness to how one is processing cultural differences and allows for the incorporation of multiple perspectives in future interactions, working towards the ability to tolerate ambiguity. Both faculty and students need to carve out time for these reflections, in order to develop intercultural sensitivity.

-

Faculty Reflective Prompts

- What is your positionality and how does it shape your standpoint? What are these concepts important in studying intercultural communication?

- Do you think there are universal human values? If so, what are they? Is the belief in universal human values inherently ethnocentric?

- What bias and assumptions might be behind your triggers?

- How do you manage your emotional intelligence in cross-cultural interactions?

- What “agreements” are present in your teaching? What agreements are intentional and which reflect assumptions you have not yet questioned?

- In what ways are reflection, revision and humility enacted or applied in your pedagogy?

- How do you use your experiences, skills, knowledge and awareness to support my students’ intercultural development?

- How can the dominance of your voice be reduced and the emergence of multicultural student voices and interpretations be enhanced?

- How can you bring multicultural voices and perspectives into my course content in substantive ways, without tokenizing students?

- With whom can I consult or collaborate with professionally to review my course materials and offer informed suggestions for improvement in a manner consistent with the values of intercultural pedagogy?

- How can I connect course content to student experiences and interest?

- How can I assess learning in ways that honor and utilize the diversity of my students and their different ways of expressing knowledge?

- What is your positionality and how does it shape your standpoint? What are these concepts important in studying intercultural communication?

-

Student Reflective Activity

Negotiating Differences Activity (Sorrells)

This activity allows students to critically reflect on their lived experience and how it might differ from other students in the classroom. The prompts listed below should be provided for individual reflection; students should not be asked to share their answers to these questions in class. Instead, you can use this activity to set the stage for a classroom dialogue that centers on bringing awareness to cultural difference and developing intercultural sensitivity.

Read the following statements and consider your response to each. On a continuum, do you strongly agree with the statement, disagree, or is your response in between?

- Hard work is all it takes for me to succeed in school, work and life.

- Big cities are generally not safe and people are not as friendly there.

- In the United States, women are treated fairly and as equals to men.

- The police are viewed with suspicion in my neighborhood.

- Going to college/university is my primary responsibility.

- Gay marriage is legalized in many states, so homophobia is increasingly a problem of the past.

- Religious freedom is what makes the United States a great country.

- I have to work twice as hard to prove I am as capable and competent as others

- For the most part, I can go pretty much anywhere in my city, town or region without feeling afraid for my safety.

- Interracial and intercultural relationships cause problems. People should stay with their own kind.

- I am one of the only ones in my family who has the opportunity to go to college/university.

- Since the United States has a Black president, the country has basically moved beyond racism.

- I can get financial support from my family to pay for college/university, if necessary.

Now that you have read the statements, consider the following:

- How do your cultural frames inform your responses?

- How are your responses related to your positionality?

- How do cultural frames and positionality intersect to shape your responses?

- Share these statements with a friend and then dialogue about how your responses may be similar or different.

- Reflect and dialogue with the other person about how our differences in terms of power and positionality impact our standpoints.

- Reflect on the assumptions and judgements you may have about people who would make these statements.

- How is dialogue with people who are different in terms of culture and positionality a step towards creating a more equitable and just world?

- Hard work is all it takes for me to succeed in school, work and life.

Language in the Classroom

The words that we use indicate our cultural and societal values. As you work towards inclusive language in the classroom, consider the following.

- When asking students to interact with each other in the classroom, either through dialogue or group work, we often use the word “respect” in our community norms. For many students, respect looks like the “golden rule”, in which we treat others as we wish to be treated, which centers the values of one’s own culture. You could have a discussion with your students about “the platinum rule” in which we treat others as they wish to be treated.

- Cultures tend to have a dominant position on the continuum of communication styles that is shaped by social norms and values. “Low(er) context” refers to a communication style in which the instructions are explicit and detailed, and assumes no inside knowledge on the part of the listener. “High(er) context” refers to a communication style in which tone, body language and context determine the words used and there are typically assumptions that the listener has inside knowledge (Cornes).

- Intercultural pedagogy encourages the faculty member to understand and employ varying degrees of low and high context depending on group composition and situational factors. While lower context communication styles can bring clarity to classroom expectations, high context styles are more relational and can center communication on tone and body language which may provide more of a more holistically welcoming and trusting environment.

- Notice if you are making references to American or dominant pop culture that students may not be aware of. You can ask your students to provide examples to illustrate course concepts.

- Make an effort to learn how to pronounce students’ names. Consider having students record a pronunciation of their name for a “Welcome” discussion board on Canvas.

- Broaden classroom conversation so that it is not US-centric. For example, when discussing the units in a science class, take a moment to note that metric units are accepted and used globally.

- Educate yourself on current issues for immigrants, first generation and international students. With increased awareness, your language regarding these issues will be inclusive for these students.

Pre-class Student Survey

Accessibility Survey

Designing and administering a pre-class student survey allows faculty to get valuable information about a student’s resources and learning needs. Sending out a survey signals interest in building relationships with students. Compiling the results and sharing anonymized data during the first week of class will help students recognize that everyone has certain needs around learning.

View SurveyLearning Outcomes

Through the use of learning outcomes designed for intercultural pedagogy, you can guide your students in becoming more self-aware, informed, open-minded, and responsible people who are attentive to cultural difference. The Intercultural Knowledge and Competence VALUE rubric created by the American Association of Colleges and Universities (AACU) offers a framework to “put culture at the core of transformative learning”.

-

"Exploring Global Citizenship" Example

INTZ 2501

The University of Denver offers a class, INTZ 2501, “Exploring Global Citizenship” is required coursework for students who are planning to study abroad.

The University of Denver offers a class, INTZ 2501, “Exploring Global Citizenship” is required coursework for students who are planning to study abroad. The learning outcomes for the course is shown below and the correlation with the AACU Intercultural Knowledge and Competence VALUE rubric. These learning outcomes are assessed with reflective assignments designed to allow each student to make progress from their unique starting point with intercultural sensitivity.

- Identify your own cultural rules and values and describe how those may interfere with the understanding of another culture. (corresponds to "Cultural Self-Awareness" on AAC&U rubric)

- Articulate the connections between identity and culture, including recognizing the various elements important to members of another culture. (corresponds to "Knowledge of Cultural Worldview Frameworks" on AAC&U rubric)

- Recognize dimensions of more than one worldview in order to understand another culture, interpret events and approach challenges. (corresponds to "Empathy" on AAC&U rubric)

- Identify and explain several key theories, concepts and frameworks related to personal development through cross-cultural interaction on study abroad.

- Identify your own cultural rules and values and describe how those may interfere with the understanding of another culture. (corresponds to "Cultural Self-Awareness" on AAC&U rubric)

Relationships in the Classroom

Creating and sustaining a positive classroom climate includes establishing ground rules for discussion and for interactions between students and between student and faculty or teaching assistants (UCLA resource). Using the suggestions below will help to bring a low context communication style and reveal the hidden curriculum for successful mastery of the course content.

-

Structured Group Work

One clear benefit of group work is that students can explore ideas with their peers in a low-pressing setting (oxford website).

One clear benefit of group work is that students can explore ideas with their peers in a low-pressing setting (oxford website). As you incorporate the ideas below, take time to walk around the classroom and affirm team processes that are incorporating all voices in the group.

Assignment of roles in group activities

When clear and distinct group roles are assigned, there is a higher likelihood of focused and collaborative interaction between students. See suggested instructions below.

- Pick 3-4 roles for the groups, such as manager, spokesperson, recorder, technician, questioner, etc.

- Provide clear descriptions for each role, along with a rubric if you intend to grade participation.

- Have the students discuss how culture impacts how they see, understand and will perform these roles to bring clarity to the instructions for the group.

- Make sure to rotate the roles periodically so that each student has the opportunity to build a variety of skills.

- Circulate to give guidance on adhering to the roles. Talk with students individually who are silencing or excluding others in their group. Intervening quickly on this matter will illustrate your commitment to the collaborative space.

- Find ways to get frequent feedback on the group dynamic. Be prepared to step in if the group needs your help to navigate social stress.

Setting Expectations

Students who have little experience working in groups may not see group work as a legitimate learning experience. Connect group work to specific inclusive learning outcomes, as described below.

- Explain the learning benefits of working in diverse groups.

- Outline your expectations around roles. Do you expect all students to perform all roles? (e.g. Do you require all students to make a presentation, submit a co-authored report or other artifacts?)

- Provide clarity about the shared tasks and individual contributions.

- Remind groups that practical arrangements should work for all.

- Emphasize that everyone will be expected to participate.

- Ask yourself if you’ve given students guidance on giving presentations before this is formally assessed. It may be a new skill for them to acquire.

Assessment

- Consider the use of group contracts or some form of peer assessment.

- Ensure your marking criteria rewards working effectively in a diverse group.

- Be clear about what is being assessed. English language competence can be a source of worry for international students.

- Encourage students to practice presentation skills before assessment.

- Consider the option to learn in groups but evaluate individually.

- Consider alternative assessments for disabled students (e.g., extra written work instead of an oral presentation if this is difficult due to a disability).

- Examine whether your criteria considers that diverse groups can take longer to reach the same level of effectiveness as mono-cultural ones.

- Ask how your assessment will recognize different group members' contributions (e.g., planning, coordinating, research, IT skills, writing skills and presentation skills).

- Pick 3-4 roles for the groups, such as manager, spokesperson, recorder, technician, questioner, etc.

-

Classroom Agreements

Making ground rules clear from the beginning is an important way instructors can help create a classroom climate that is explicitly centralizing for diverse students.

Making ground rules clear from the beginning is an important way instructors can help create a classroom climate that is explicitly centralizing for diverse students. If possible, instructors should devote a portion of the first class to developing ground rules along with their students and have the rules incorporated into the class syllabus so that there is a written copy or the rules can be emailed to students. If time constraints make such discussion impractical, ground rules that acknowledge the importance of respect for diverse views should be included in the syllabus. By actively and explicitly signaling support for diverse views, faculty can build an inclusive space from the beginning.

The Inclusive Pedagogy Module offers examples of activities and example agreements under “Ground Rules” as well as “Norms of Collaborative Work”.

Transparent Assignments

The Transparency in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education project (TILT), founded by Dr. Mary-Ann Winklemes, has provided a framework for re-designing assignment prompts such that students have a clear understanding of faculty goals and expectations. See the “Videos” section below to hear more about the project.

When building a template for a transparent assignment, include the following:

- The purpose of the assignment, which included the skills that are being practiced and what knowledge that the student will gain. Learning outcomes could be included.

- The task of the assignment, including what the students will do and clear steps to follow. Include any instructions on how to be successful on these tasks.

- The criteria for success which should include a rubric and annotated examples of previous student work.

“The slippery nature of culture, the flow of cultural histories, and positions among the complex communicative paths of interpersonal dyads, social and professional groups, institutional structures and geographic and affiliative movements, textures pedagogical interactions of all kinds, even when culture is not directly acknowledged or treated as a topic of investigation within a classroom”

(Sandoval and Nainby, Casey’s book “Critical Intercultural Communication Pedagogy”, 2017).

Supportive Resources

Articles

Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity

Describes the DMIS model derived by Milton Bennett, the various stages and how to measure intercultural sensitivity both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Read the Article

After Anti-Asian Incidents, Colleges Seek to Reassure Fearful International Students

Videos

Special Contribution

The following people helped to design, build and edit this page:

- Casey Dinger (he/him) Executive and Academic Director for Internationalization

- Becca Ciancanelli (she/her) Director of Inclusive Teaching Practices

-

References

Bennett, J.M., & Bennett, M.J. (2004). Developing Intercultural Sensitivity: An Integrative Approach to Global and Domestic Diversity. Sage Publications, Inc.

Bennett, M. J. (2004). “Becoming interculturally competent”. In J.S. Wurzel (Ed.) Toward multiculturalism: A reader in multicultural education. Newton, MA: Intercultural Resource Corporation.

Calafell, B. M., Chuang, S., Cooks, L., Cramer, L., Harris, T., González, A., ... & Yep, G. (2017). Critical intercultural communication pedagogy. Lexington Books.

Chatelain, M. (2018, Oct 21st). “We Must Help First Generation Students Master Academe’s ‘Hidden Curriculum’”. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/we-must-help-first-generation-students-master-academes-hidden-curriculum/

Cornes, A. (2004). “'Important Values Orientations for the Sojourner" in Culture from the Inside Out: Travel and meet yourself. Intercultural Press.

Elliot, D.L., Baumfield, V., Reid, K. & Makara, K.A. (2016). Hidden treasure: successful international doctoral students who found and harnessed the hidden curriculum. Oxford Review of Education, 42:6, 733-748.

Guy-Evans, O. (2022, May 11th). “What is Ethnocentrism and How Does It Impact Psychology Research?” Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/ethnocentrism.html

Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally Responsive Teaching & the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Corwin/Sage.

Lee, A. (2017). Teaching Interculturally: A Framework for Integrating Disciplinary Knowledge and Intercultural Development. Stylus Publishing.

Misawa, M. (2010). “Queer Race Pedagogy for Educators in Higher Education: Dealing with Power Dynamics and Positionality of LGBTQ Students of Color”. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3 (1), 26-35.

National Geographic. (n.d.) Globalization. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/globalization

Oxford Brookes University. (n.d.) Inclusive Group Work. https://www.brookes.ac.uk/staff/human-resources/equality-diversity-and-inclusion/guides-to-support-inclusive-teaching-and-learning/inclusive-small-group-work/

Sorrells, K. (2020). Intercultural communication: Globalization and social justice. SAGE Publications, Incorporated.

Trebisacce, G. (2019).” Intercultural Pedagogy: A Methodology for Contemporary Society”. European Journal of Social Science Education and Research, 6(1), 30-32.

Unesco. (n.d.) Hidden Curriculum. http://www.ibe.unesco.org/en/glossary-curriculum-terminology/h/hidden-curriculum